For private wealth clients, the consideration of tax liabilities adds another wrinkle to already complex investment decisions. It is vital for high-net-worth individuals and families to weigh the tax implications of any changes to their portfolio as taxes can erode gains, hindering their investments’ ability to meet their financial objectives.

Fortunately, it is relatively simple to quantify this trade-off to make better informed investment decisions. Private wealth clients with the discipline to incorporate this type of analysis typically benefit from an increase in after-tax performance.

THE TAX MAN COMETH

As taxable investors, private wealth clients contemplating making a change or funding a new investment (unless the funding source is cash) need to evaluate their current investment position relative to the new or adjusted position less any tax liability. To make this assessment, they need to know the cost basis, the market value, and the expected return of the current position, as well as the expected return of the new or adjusted position, and the marginal tax rate that will be paid on realized gains.

For instance, take the example of a Massachusetts investor who has established a $1,000,000 position which has appreciated to $1,250,000 (Exhibit 1). Based on this increase in value, the investor may believe it is time to liquidate the position.

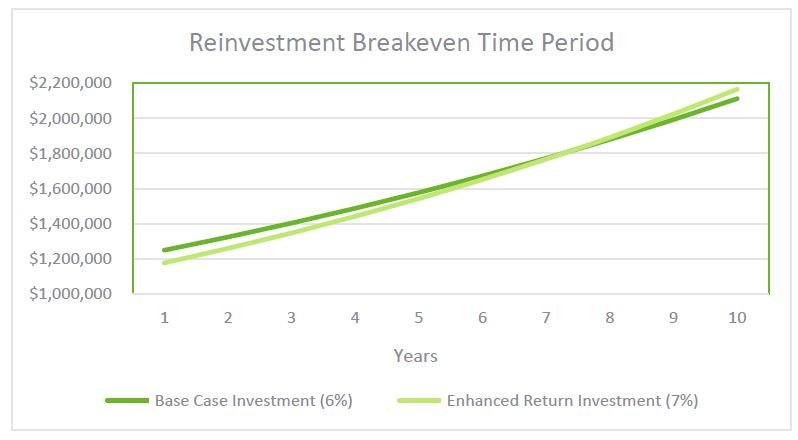

However, if the position were fully liquidated, a tax liability of $72,250 would be incurred (1). If the net proceeds of $1,177,750 were invested in a position that was expected to generate an additional 1% return compared to the current investment (assuming 7% compared to 6%), and allowed to compound unencumbered, that is, no turnover generating additional tax liabilities, it would take seven years just to recoup the tax liability!

In the prior example, we assumed a long- term capital gains rate. If we were to take a more punitive position and assume a short- term capital gains rate, the break even period would be nearly twice as long.

In fact, when looking at the potential difference between a current position’s expected return and the new position’s expected return (the return delta) it quickly becomes clear that making adjustments in the hopes of capturing incremental return may not be the right decision, particularly for those with short-term gains, significant embedded gains or high tax rates at the state level.

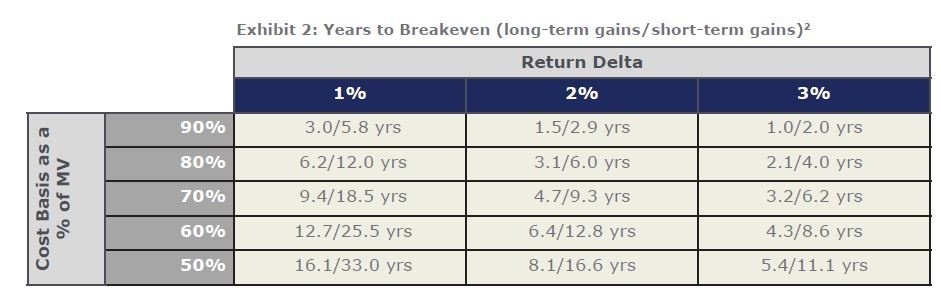

In Exhibit 2, we look at the number of years required to recoup the tax cost based on the level of embedded gains—cost basis as a percentage of market value—and the expected return delta between the existing investment and the proposed investment for both short-term and long-term holdings.

The same type of break even analysis can also be used to evaluate the impact of portfolio shifts, such as tactical deviations away from a policy benchmark, or changes within the portfolio such as an upgrade from one manager to another.

In either situation, the holding period, the level of embedded gains and the return delta are the primary determinants of the break even time for a given tax liability; changes to the nominal return assumptions have a minor impact.

It is vital to evaluate this trade-off, especially given the wide range of possible outcomes for most investments— for example, the S&P 500 Index has generated annual returns as high as 52% and has lost as much as 37% over the past 80 years. To this end, it is essential to balance the known tax liability against the unknown level of confidence in the expected return delta.

A BETTER DECISION-MAKING PROCESS

Re-framing a tax liability in terms of a known one-time expense relative to a break even time frame can help private wealth clients make more informed decisions as they seek to deploy and redeploy capital. It underscores the importance of keeping in mind the impact of taxes when making investment decisions with regards to asset allocation and manager selection.

Although the burden of taxes creates a higher hurdle for private clients than most institutional investors, it is not insurmountable. Wealthy individuals and families should never be deterred from making changes to their portfolio when they believe it is the right thing to do. That said, the decision-making process will benefit from a disciplined approach and thoughtful consideration of the anticipated taxes, potentially bolstering post-tax performance and enhancing their investments’ ability to meet long-term financial objectives.

(1) Assumed total tax rate of 28.9% (Federal Long-Term Gain of 20%, 3.8% Net Investment Income tax, 5.1% Massachusetts State Tax)

(2) Assumed highest marginal rates of 28.9% (long term) and 52.8% (short term) for a Massachusetts investor.